Since then, she’s become the first Black woman to hold the Commodoreship at a Los Angeles Yacht Club, become a 50-T Master Captain and certified sailing instructor, started a community sailing program, and participated in major regattas like the Transpac.

Rogers was always an athletic, although solitary, person. Skiing, bike riding, marathoning – you name it. As a child growing up in the suburbs during the civil rights and bussing movements, she was often the one “different” kid, causing her to gravitate to solitary activities.

“Most people wouldn’t believe it now, but when I was a kid, I was a total introvert because I was traumatized by a lot of overt and systemic racism,” said Rogers. “I was subject to overtly troubling situations that should never happen to a child.”

Despite that trauma, Rogers has gone on to break barriers. It was Roger’s confidence in her sailing and leadership abilities, bolstered by sailing courses and her involvement in women’s sailing programs, helped her enter this predominantly white, male space.

“I was feeling so confident in myself, our boats and our abilities – and I saw this need for representation as a woman and as a person of color,” said Rogers. “That feeling inspired me to speak up and start bringing in new members that brought diversity and financial gain to the club.”

At first, Rogers began sailing with her husband Bill, a member of the Los Angeles Yacht Club (LAYC) who owned a 70-foot racing boat. They often cruised to Catalina Island and other coastal destinations, but Roger’s husband was the one in control of the boat.

“I was always just the ‘wife,’” said Rogers. “But one day I realized if anything should happen to my husband, I needed to know how to get this 70-foot boat back to shore safely. I decided it was time for me to learn on my own.”

Rogers enrolled in sailing school, where she was able to re-learn the basics of big boat sailing in a new, more relaxed environment. Her course instructor, a retired Navy man, approached sailing in a way Rogers had never experienced before – no yelling, no ignoring, only calm explanation of the facts. That’s when Rogers knew she wanted to spread that experience to others.

“I wanted to be that grounding influence on beginner sailors so they could have the awesome experience I had when I first tried sailing,” said Rogers. “I wanted to be in his position and introduce people to sailing in a calm way, so they’d keep coming back.”

As Rogers got more involved in sailing, both on her own and with her husband, she became a member of the LA Yacht Club in 1999. After some digging, she discovered that she was the first Black member of LAYC – one of the oldest yacht clubs on the West Coast. Because of her history being the only Black person in all-White spaces, the idea of being the “odd woman out” didn’t bother Rogers too much, at least at first.

“It offered me an incredible opportunity for my own personal development, especially since I grew up a very solitary person; so, when I first came in, I made myself very small,” she said. “I recognized, too, that I came in with my White spouse who was already a member, so I was more readily accepted.”

After joining the club, Rogers wanted to put her sailing skills to good use. Not content to sail only when her husband was around, she began looking into communal boats for the club that members without their own boats could use – to no avail. Shelving that idea for later, she went on eBay, and bought her first boat, a Cal 25.

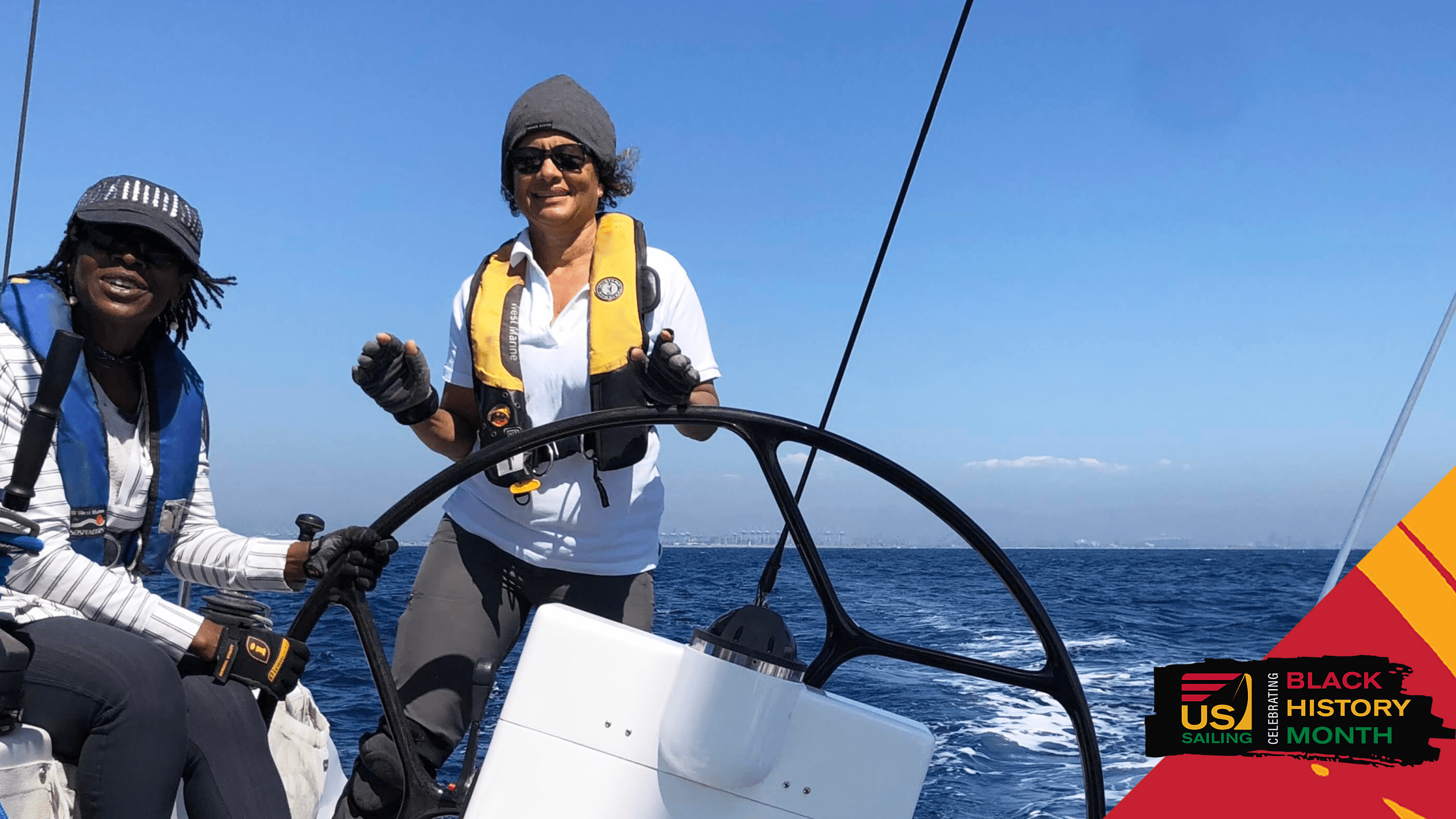

Rogers began inviting other women to come sail with her, independent of their husbands. Women on the Water asked her to contribute to their program with that boat, until eventually they were cruising to Catalina by themselves. Watching these women gain independence and enjoy themselves on the water inspired Rogers to begin drafting a business plan for a community sailing program at LAYC.

At first, the idea was met with resistance from some of the club members, who saw it as introducing “undesirables” into the club’s membership. Eventually, Rogers was able to convince them that this would be good not only for members of the community, but also for the club’s bottom line.

“It was so contrary to what this exclusive club had been for over 100 years,” she said. “But once they realized this wasn’t going to be a social or drinking kind of program, and that it would bring in new, paying members, they accepted it. Over the years my husband and I connected tons of people to the water who wouldn’t have otherwise had access.”

As Rogers continued to build this community sailing program at LAYC (including donating her own Cal 25 to the fleet), she was asked to join the board of directors, eventually climbing the ranks of flag officers to become the commodore in 2019 – a first for the club.

While most people saw this as a groundbreaking achievement, the Black Lives Matter movement and the election in 2020 cast her position as a Black woman in leadership and the community sailing program that she built in a new light.

“2020 caused a lot of division, in the world at large and in sailing, so what I had been doing bringing all these people in became seen as a threat,” said Rogers. “And me, being the commodore and identifying as a Black woman, caused some problems. For some it was an issue for me to make that proclamation.”

To Rogers, the only way to widen the sailing experience and get BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) involved is to break down barriers – both physical and social – around sailing and the water.

“We have to start from the beginning with basic water access. In California, the waterfront has been redlined going back hundreds of years. For us, it was so hard to grow up near the water. To do that, you have to buy a multimillion-dollar house; even then, it’s still hard to get in,” explained Rogers.

Many beach communities in California physically prevented Black people from owning land – and if they were able to purchase land, it could be stolen and redistributed to White landowners or the government. For example, Manhattan Beach, CA recently began the process of returning land that was seized from a Black beachfront resort by imminent domain in 1924. The land, taken from the Bruce family – who were seen by their White neighbors as “great agitation” – is now worth millions of dollars.

Rogers also advocates for yacht clubs to do outreach outside of just junior programs, or regattas that happen once a year. As the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion chair for Southern California Yachting Association, Rogers encourages clubs to reach out to professional organizations – like Black sororities, fraternities, Law and business associations – and invite them in for events or to tour the club.

“Give them a chance to experience what you have to offer. This way, you’ll likely bring people in who you have something in common with, who are even in your professional network, you just don’t know it yet,” she said.

Overall, for Marie Rogers, it’s about bringing people together.

“I want people to understand we have so many similarities,” said Rogers. “Yes, we also have our differences; but I really feel that once you get people on a boat, all the sudden everyone is having a good time and those differences, whatever they may be, fall away.”