Since she was 3 ½, Stephanie Helms knew she was a girl.

At that age, her mother was helping Stephanie complete physical therapy for a burn injury. She complimented Stephanie on an exercise well done, saying, “good boy!”

“And I said, ‘no, girl,’” said Helms. “All my life I’ve known that I was transgender, although I didn’t have the words for it for many years.”

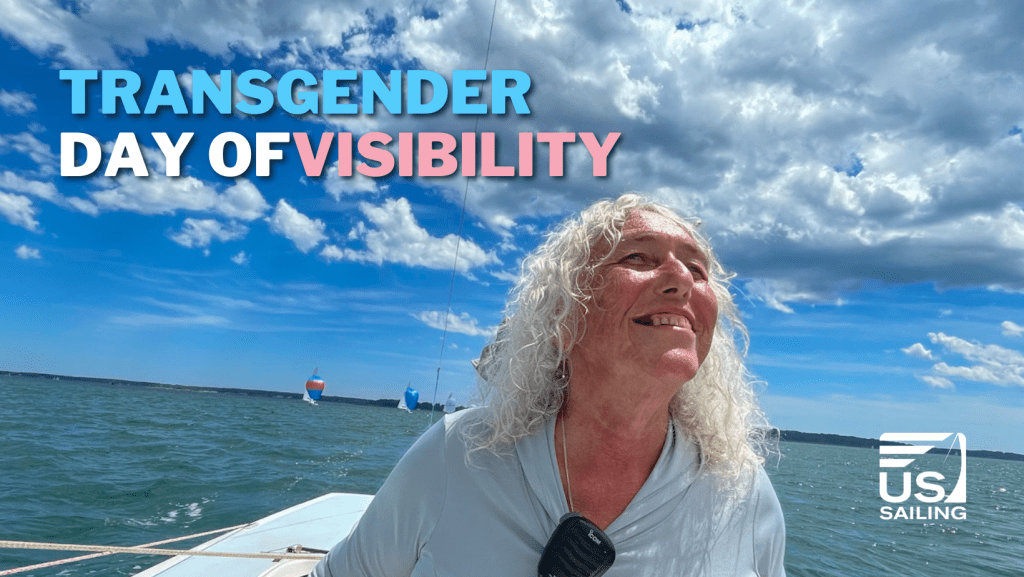

If you’ve been around the New England sailing community, you’ve probably encountered Stephanie Helms. Helms is a prolific sailor and industry professional, well known as a race official and in the J/24 class. She has worked for Shore Sails, Sail Maine, and now owns her own sail repair shop in Yarmouth, Maine.

She is also a fierce advocate for transgender people in sport, having studied the issue closely. Helms is a member of the US Sailing DE&I committee and the transgender task force.

Both her personal and professional experience give Helms a unique platform to advocate for trans people in sport. With the Transgender Task Force, Helms has assisted in crafting gender identity policy that conforms to the International Olympic Committee’s recently announced framework, which gives each sport the ability to determine their own gender categories and make regulations on where transgender people fit in.

“The key thing people ought to keep in mind is what they see about the issue is shaped by agendas in the public press, but when you really dig into it, it’s not as cut and dry as you think,” said Helms. “Sports are a human right – people should be afforded the ability to participate, no matter what.”

Helms learned to sail at a summer camp where her mother was employed as a nurse. One of the other camp staffers took her out for a couple rides on his Sailfish and offered her the chance to use the boat on her free days. “This was the era before helicopter parents,” noted Helms, chuckling.

“Without much instruction, I decided one fine afternoon I would take the boat out,” she said. “I sailed downwind all the way on one end of the lake and then turned around and had to sail upwind to the other end of the lake, flipped the boat over half a million times, laughing all the while. Although it was somewhat painful, I enjoyed it a lot.” Throughout her youth, Helms returned to that lake, becoming more confident in her sailing abilities.

As she got older, her interest in sailing waned. Neither her high school nor her college, Brandeis University, had sailing teams. It was not until Helms was offered a job at a sail loft post-college that she came back to the sailing world.

“I fell into sailing as a career quite accidentally,” Helms told the Trans Sporter Room podcast.

Throughout the early part of Helms’ sailing career, she kept her identity hidden, presenting as male to her family, friends, and coworkers. Her early insistence of womanhood was not well received by her family – after all, it was the 1950s – so she learned to suppress her female identity and “become a boy,” as she told the Trans Sporter Room podcast.

“As bad as the pushback is now, there was very, very little understanding either on the part of the medical profession or in the general public at large of what being transgender was,” said Helms. “There was this feature of my personality that I learned, ‘you just can’t go there’ which caused a great deal of struggle.”

Helms was 44, a part owner in the Shore Sails loft in Maine, when she decided enough was enough – it was time to transition in the public eye. “I just reached the point where it’s like, I can’t do this anymore. It’s just not going to work,” she said.

Helms began the long, slow process of coming out to friends, family, and coworkers after beginning gender affirming hormones, also known as hormone replacement therapy (HRT). While “coming out” can be a public display for some, for Helms, it was mostly one-on-one discussions with those close to her.

Transition caused significant disruption in Helms’ life – she sold her share of the sail loft business and left the sport following gender affirming surgery that kept her off the water for nearly a year. She was also left wondering if those in the sailing community would be welcoming to her after her transition.

“Honestly, I didn’t really think that folks would want me to sail again,” she said. “But in 2004, people started asking me to sail, and it felt natural to jump back in. There were several people who were incredibly supportive, some who were the last people on Earth that I would have thought would be… some old white conservative guys, who for some reason or another, I think out of an abundance of compassion took me under their wings.”

Soon after, she began sailing on the J/105s and J/24s, participating in the North Americans and several Block Island Race Weeks. Helms also began a relationship with Sail Maine, a program she helped build to the success it enjoys today, and got back into the sail making business, opening her own sail repair shop.

While being transgender can be a struggle, according to Helms, it has been worth it to live openly as her true self.

“People talk about gender dysphoria, but there is such a thing as gender euphoria,” said Helms. “It’s quite joyous to be able to live and move and be comfortable in your own physicality.”

If there’s one thing Helms wished people knew about being transgender is that it really isn’t that different than being cisgender – meaning a person whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex.

“All trans people want to do is feel the freedom to enjoy life the way most people do – it doesn’t hurt anybody to let them live their truth,” she said. “You may find that if you do let them live their truth, society will be all the richer for it.”